(01) Essay

Jahkarli Romanis,

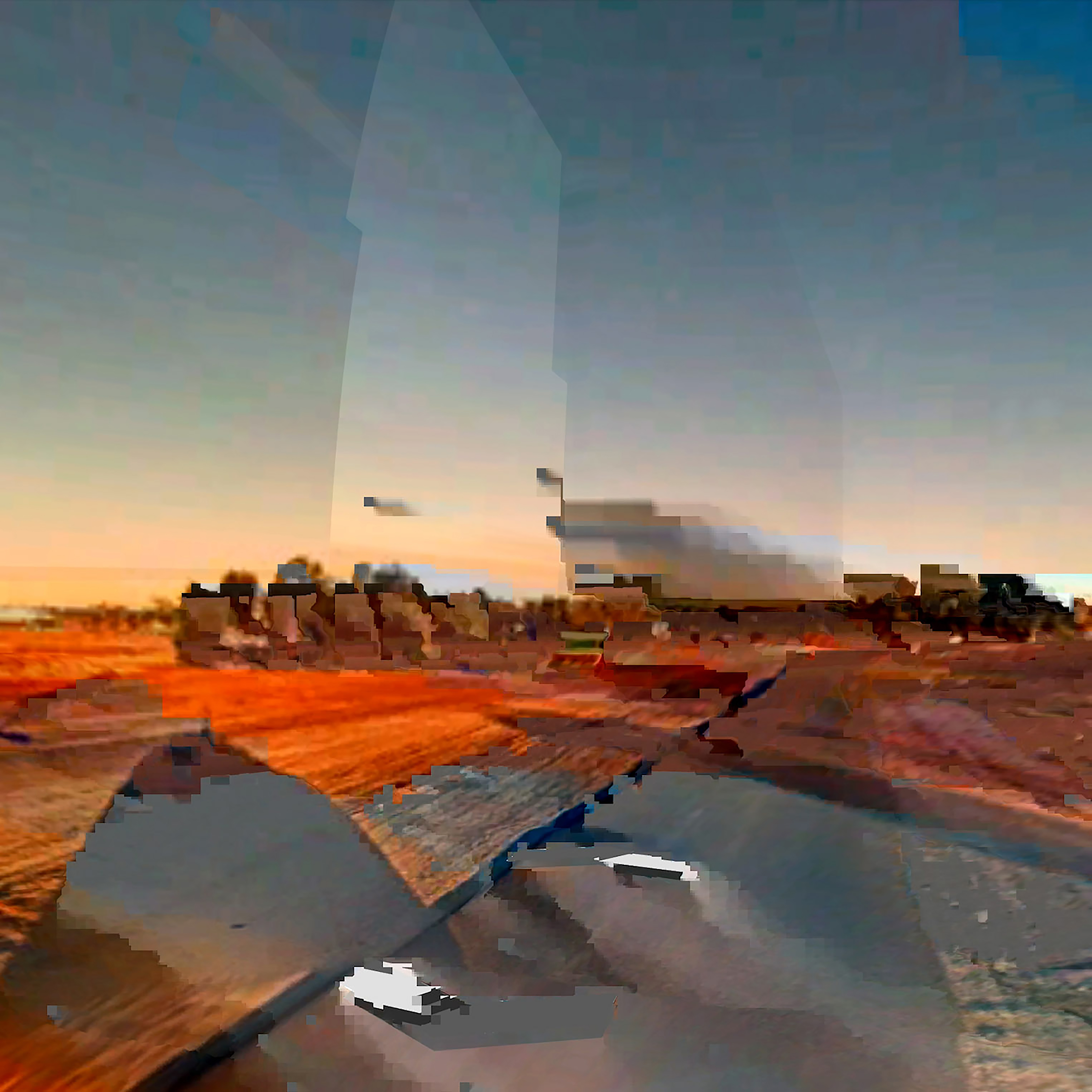

(Dis)connected to Country

2019–ongoing

‘When the landscape becomes unrecognisable; when you actually don't know that you’re looking at a landscape when it glitches to the point of opening up a void—this is what I come back to.’

Jahkarli Romanis is a Pitta Pitta woman and Naarm (Melbourne) based artist. Raised on Wadawurrung Country in Torquay, Romanis moved to Naarm to continue her tertiary studies in 2018. (Dis)connected to Country began as a visual engagement with Romanis’ ongoing process of displacement from her ancestor’s Country. ‘It was quite literally about my disconnection to Country. I grew up in Torquay—Wadawurrung Country—and Pitta Pitta has always felt very far away.’ This notion of dis/connection became Romanis’ mode of aesthetic and material intervention. Part of her practice-led PhD research, (Dis)connected to Country focuses on representations of self and place through photo-making technologies. The place-driven aspect of the project (our focus) interrogates the biases and limitations encoded in Google Earth’s construction of the so-called Australian landscape. The series visualises moments where Google’s infrastructures of seeing break down and show how alternative relations to the ‘environment’ endure in the seams of the colonising project.

‘The place aspect of the project started during COVID,’ says Romanis, ‘when I started thinking about alternative ways of going to Country or being on Country, so to speak. And so I went there through Google Earth.’ Romanis became interested in how the colonial concepts of ownership and control are embedded in such Western mappings of landscapes, rendering Indigenous ways of knowing invisible. While Google Earth’s familiar perspectives of ‘street view’ and ‘satellite view’—the latter implicated in military histories of aerial surveillance—are often thought of as ‘neutral’ or ‘scientific’, Romanis seeks to highlight the subjectivity that produces the images. ‘There are knowledges that are not included,’ she says, ‘this [is] is harmful to First Nations people and a national understanding of place.’

In (Dis)connected to Country’s evolving series, Romanis works with screenshots from Google Earth’s depiction of Pitta Pitta Country in their transition between ‘Street View’ and ‘Satellite View’. This distortion provides a vivid contrast to the clean and functional aesthetic expected from Google Earth. ‘I’m interested in this glitch showing this kind of colonial construct is breaking within itself . . . It’s not functioning the way that it should be within this technology,’ Romanis says. These in-between moments not only offer this critique of colonial visuality but orientate us towards relations to ‘the environment’ that, like the glitch aesthetics of Romanis’ practice, pervade such interfaces. While Google Earth’s lens obfuscates Country, Romanis’ practice, in turn, renders Google Earth’s imagined landscape unrecognisable—exposing an ‘in-between space, a technological glitch, a void’ that gestures towards alternative modes of endurance outside the colonial project. ‘Regardless of whether you can see [the relationship to Country] or if it’s acknowledged or represented, it’s still going to be there,’ Romanis says.

While the series interrogates the myth of ‘terra nullius’ concerning the Australian landscape, Romanis is also concerned with addressing the ownership of imagery. ‘[Google Earth is] expecting people to interact with these images in a very specific way, while enforcing this interaction by controlling what people actually can do with the with the images.’ According to Google Earth’s permission guidelines, the project is infringing copyright. ‘Technically, I’m not allowed to sell my work, because I am highlighting there are problems with the technology’. Google’s copyright enforces the company’s position as owners of the images, yet their process of image production, Romanis argues, works to obscure their accountability. ‘Historically, maps were attributed to the human hand making it, now we have technologies producing them . . . we probably have coders who don't know anything about cartography, but are expected to make these programs.’ Obscuring further the notions of accountability and authorship is the company's practice of subcontracting. ‘Google Earth employs different satellites, and they’re technically not Google Earth satellites. Other corporations own them,’ says Romanis. While claiming to represent ‘place’, the images are implicated in a global, if not thermospheric, supply chain—a position which might offer a juxtapositional reading of the ‘void’ the work generates.

While (Dis)connected to Country has so far focused on the political aesthetics of Google Earth, Romanis next plans to engage with alternative methods of mapping that might reflect a relational feeling to Country. This approach begins with visiting Country and speaking with Pitta Pitta Traditional Owners. ‘The next step is visiting Country . . . I’m taking my mum as well, so it’s a family affair. I didn’t grow up on Country, and my family has been really dislocated from this landscape for such a long time. Next to exploring how we might subvert Western representations of Country, it’s through this project that I'm figuring out my own identity and how I connect with Country.’

(02) Dialogue

Dialogue between

Jahkarli Romanis and Taylor Mitchell

Taylor Mitchell (TM): Firstly, I want to acknowledge that a lot of this project took place on Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land, and that sovereignty was never ceded. I also want to thank you for speaking with us about your important work.

My first question is, can you describe your ongoing project (Dis)connected to Country and how your work on place is situated within this?

Jahkarli Romanis (JR): (Dis)connected to Country is an ongoing project that started in 2019. It was quite literally about my disconnection to Country. I grew up in Torquay—Wadawurrung Country—and Pitta Pitta has always felt very far away. It was about thinking about how I might submerge myself back into the landscape through photographic means. I was making self-portraits and mm, combining those with images that I've made of Country. The place aspect of the project started during COVID, when I started thinking about alternative ways of going to Country or being on Country, so to speak. And so I went there through Google Earth.

It was really when I started to understand what the technology was doing in terms of representing landscape and the sort of implications involved with that technology—this is when I started shifting the project towards place.

TM:

Thank you so much. Your work

documents Google Earth’s depiction of Pitta Pitta Country, located in

Queensland, Australia, in transition—combining ‘Street View’ with ‘Satellite

View’. Can you speak to how the resulting ‘glitch’ aesthetics interrogate

colonial constructions of landscape and the environment and the myth of ‘terra

nullius’?

JR: It’s a big question! Maps—Western maps, I should say— have a history with colonialism in that they're coming from a position of ownership. To have a map of a place is to kind of own that place essentially. And so Google Earth has quite literally continued this colonial system of mapping and ownership in that way, while publishing, images of the land of the world, accessible to the public. It’s important to think through how their imaging technology, like ‘Street View’ and ‘Satellite View’ came about. In particular, satellite and aerial view came out of the military-industrial complex—it was about having control over other states, essential about spying. So the project became thinking about how these technologies are rooted in colonial concepts of ownership and control.

It turns of working with glitching, this was in response to our expectation for Google Earth as very clean—you know, it’s meant to function as a way of looking at the landscape. I’m interested in this glitch showing this kind of colonial construct is breaking within itself. It’s wavering. Not solid. It's not functioning the way that it should be within this technology. When we think about ‘terra nullius’, meaning ‘no man’s land’, Google Earth is depicting the landscape from a strange viewpoint as a machine made image—and ownership is very interesting when it comes to this.

TM:

The broader

project of enduring environments is concerned with examining aesthetic interventions into how the environment is

governed and produced the colonial project. Your practice documents what

you call a ‘void’—can you speak a little more about how the project engages

with ideas about what we can’t see?

JR:

What we can’t see is

absolutely this strong connection to Country, and the relationality between

self and Country which you can’t see, but it’s more something that you feel.

Country is such an all encompassing

thing and it’s been reduced through these screen technologies. I’m also

interested in how, in Google Earth spaces, there is no acknowledgement of

Traditional Owners. But regardless of whether you

can see [the relationship to Country] or if it’s acknowledged or represented,

it’s still going to be there.

TM: Thank you, Jahkarli. I was wondering if you could speak a little bit more about how the global corporation and machine learning are changing ideas around authorship.

JR:

For sure. Historically,

maps were attributed to the human hand making it, now we have technologies

producing them, making it very difficult to actually place

accountability. I suppose you know that Google Earth employs different

satellites to make the images, and they're technically not Google Earth

satellites. Other corporations own them.

TM:

Wow, I didn’t know that. But

that’s very interesting. It reminds me of the global shipping industry, and all

the different contracting that diffuses accountability there as well.

JR:

Yeah, it’s insane. And when we are talking about

these issues, it makes it very hard for people to make contact with someone in

particular who can make changes because there is such a huge huge production

line involved with these maps, you know, we probably have coders who don't know

anything about cartography, but are expected to make these programs. It becomes

a slippery slope.

TM: Can you talk a little more about the myth of neutrality and how the project interrogates this?

JR:

Definitely. I believe a big issue with sort of

these new technologies, and Western ways of mapping, is that it reproduces a

very set design standard, which people have started accepting as neutral

because these standards are coming from a ‘scientific’ perspective. My work is

really about highlighting that they are subjective. There

are knowledges that are not included, and this subjectivity in Western map

creation is harmful to First Nations people and a national understanding of

place as it only comes from one perspective rooted in colonial values.

TM:

Thank you for that. In this project, are you working with the moving image as well or is it predominantly

screenshots of the viewpoints in transition?

JR:

Yeah. So I’ve been. I’ve been working a little

bit with moving images well because whilst the screenshots really great, moving

image adds another dimension to it within the Google Earth realm. And it’s maybe

a bit easier for people to kind of understand what it is that they're actually

looking at when we're sort of moving through. This is kind of like another

landscape, I suppose.

TM: Could you speak a little bit about your choices of imagery so far?

JR:

I’m just interested in what looks weird—these

screenshots offer a portrayal of the technology degrading or breaking down, or

not complying to, you know, these clean-cut representations that you expect to

find. When the landscape becomes unrecognisable; when you actually don’t know

that you’re looking at a landscape when it glitches to the point of opening up

a void—this is what I come back to.

TM: Thank you! And according to Google Earth’s permission guidelines, your project is infringing copyright. Can you speak to how settler colonial law works to produce specific ideas of the environment and how your work on Place in (Dis)connected to Country examines this?

JR:

I think it comes back to colonial control in a

way. They’re making these images, and are expecting people to interact with these images in a very specific way, while enforcing this interaction by controlling what people actually can do with the with the images. Technically, I’m not allowed to sell my work, because I am highlighting there are problems with the technology. You’ll also find with a lot of the Google Earth imaging their watermark pretty

much like everywhere. So that’s something else that comes into like choosing

image—trying to remove that watermark, and find spaces it isn’t included.

TM: It’s scary how much power they have in mediating reality, you know, in an aesthetic sense, but also in a legal sense. Can you tell us a little bit about the project in the context of the PhD? And where you are planning on taking the practice-led research next?

JR:

It’s such a tricky project to navigate, because I am engaging with these institutional spaces and ideas and trying to combine them with Indigenous Knowledges and perspectives, and those sorts of things are very hard to kind of bring together. But also, it is through this project through which I feel privileged to be reconnecting with Country. The next step is visiting Country, forming relationships with mob and speaking with Traditional Owners to more broadly understand mapping from their perspective, centring relationality to Country. I think it will be a long and ongoing conversation over the course of my PhD, but this first trip I’m taking my mum as well, so it’s a family affair. I didn’t grow up on Country, and my family has been really dislocated from this landscape for such a long time. Next to exploring how we might subvert Western representations of Country, it’s through this project that I'm figuring out my own identity and how I connect with Country.

Jahkarli Romanis, (Dis)connected to Country. [link]

Jahkarli Romanis, Google Earth is an illusion: how I am using art to explore the problematic nature of western maps and the myth of ‘terra nullius’, The Conversation [link]

Jahkarli’s practice aims to subvert and disrupt colonial ways of thinking and image making. She utilises her research and artwork as tools for investigating biases encoded within imaging technologies and as a way of connecting to Country and family. Jahkarli was a finalist in the 2023 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Awards and has an upcoming solo exhibition part of PHOTO2024 at Hillvale Gallery.