(01) Essay

Tributaries,

Silurian Geology

Silurian Geology is an episode in a

series of ‘video moments’ created by Tributaries—an ongoing, collective project that engages walking as a

site-based critical and creative practice. The project began during Victoria’s

Covid-19 restrictions in 2020–21 when artist Geoff Robinson and

architect and artist Ying-Lan Dann made audio recordings of their daily

conversational walks that followed a hidden creek tributary that runs submerged

from Royal Park to the Lower Moonee Ponds Creek in North Melbourne—Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung land. In Dann’s words, they ‘met as neighbours emerging as

collaborators through a shared interest in the layered conditions of where they

lived’. They were later joined by fellow neighbours, landscape architect Saskia

Schut and artist Benjamin Woods and met with Wurundjeri Woi-wurrung elders to seek

permission to continue their practice. The project challenges conventional

documentary practices of ‘capturing’ visible evidence of change. Instead, they

approach the complexities of the durational layers of the creek tributaries,

including the geomorphological transformations, colonial impacts, and

ecological changes through multiple modes of listening, viewing, touching, and

smelling with no set outcome or format in mind.

Since European

invasion, the natural environment and the form of the Moonee Ponds Creek’s

channel have undergone dramatic modification. In the 1880s, the shallow, marshy

ponds became sewerage dumping grounds while tributaries were channelled into a

network of underground waterways to create land for industrial development. The

1950s and 1960s saw the conversion of the creek’s chain of ponds into a linear

concrete stormwater drain to prevent flooding of installed residential areas. Silurian Geology conveys the

collective’s interaction with a deeply incised section of the creek where an

outcrop from the Silurian geologic period—a remnant of an ancient ocean

trench formed by a massive glacial melt—butts

against the steep, smooth sides of the modern concrete casing. In

Robinson’s words, the video produces ‘different vantages of the old and new

rocks that shape the flows of the creek’s water… different views across time,

but also spatially with different positions and locations of viewing and

interpreting’.

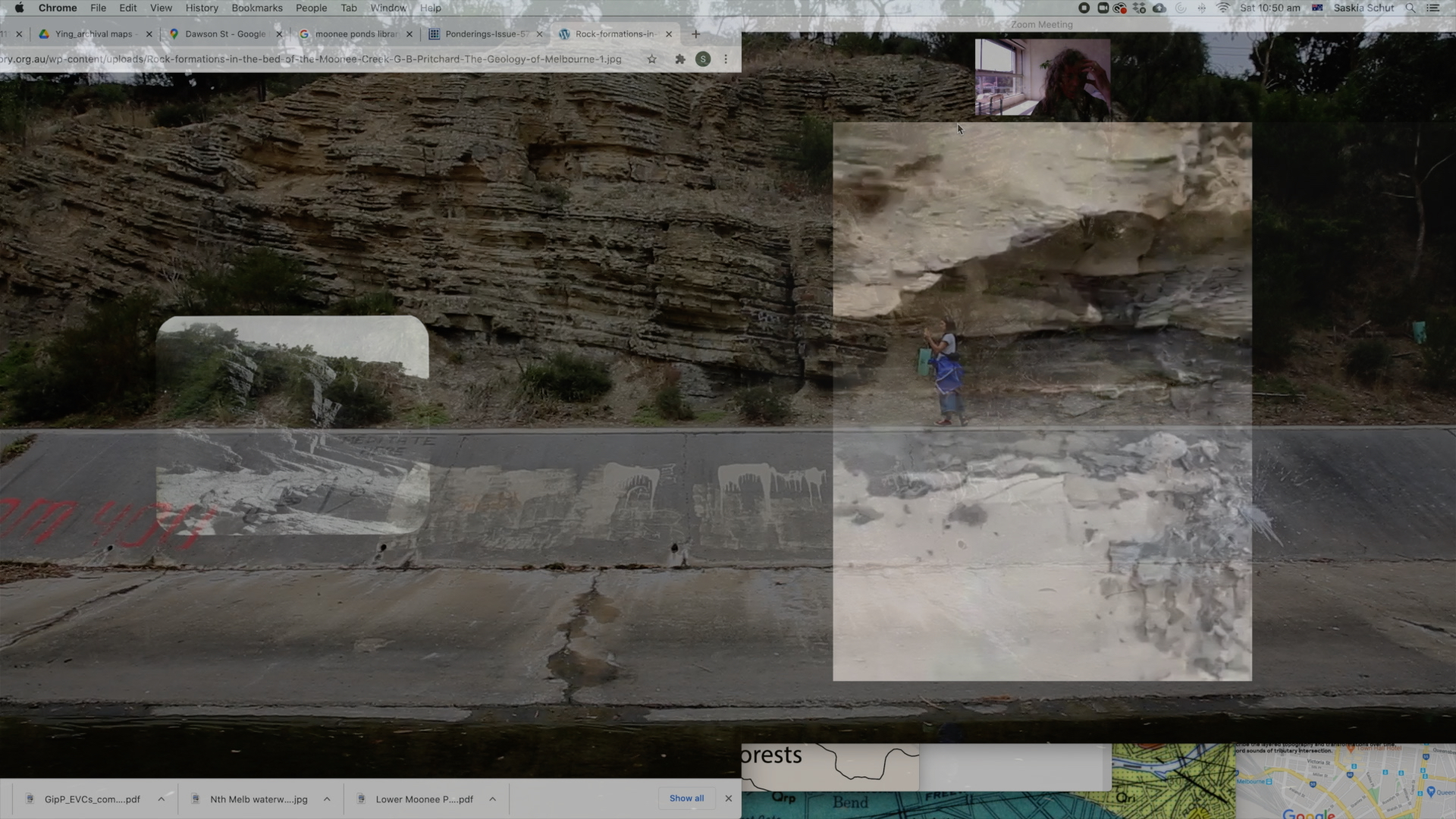

In the opening

shot, Robinson is on one side of the creek, viewing Dann, and they are

listening—‘hearing the creek’ And then, as Robinson says, there is the image

across from the creek, where we see Dann approaching the Silurian outcrop. She

uses a mobile camera as a kind of digital stratigraphic tool to scan the

exposed undulating layers of mudslide, siltstone and shale glued together over

millions of years; a rough surface defaced by graffiti. This scene then morphs

into a new vantage of Schut encountering this section of the creek remotely

(due to imposed pandemic restrictions) via the location recordings. A screen

capture mirrors Schut at her desktop studying a composite layering of close-ups

of the rock juxtaposed against a vertical wall of scrolling images that Schut

has extracted from Melbourne’s colonial archive, pausing on a black and white

photograph showing the outcrop and sandy banks of the creek prior to human

modification. As a video moment, Silurian

geology produces a temporal impression of colliding time: the deep time of the Silurian rock interpenetrates a present

time of video editing to make visible the historical legacies of the creek.

Silurian geology’s imaging of

encountering deep time in this way prompts us to reflect on our understandings

of time in relation to the environment and of the times. Although ‘geologic’ and ‘deep’ time are often used

interchangeably, they refer to different European concepts of time. Geologic

time highlights the way geoscientists measure time through a coarse time scale

that stretches into millions of years. Deep time, coined by Thomas Carlyle in the

1830s and later popularised by the writer John McPhee (1981), emphasizes the

dizzying effect of encountering geological events of a temporal scale so vast

that they annihilate the scale of human lives; a disorienting confrontation

with a past time before human experience and existence. In these times, however, encounters with past deep time surely also

make present the pressing question of a deep time future of climate change and

the Anthropocene—a confrontation with the new status of humans as ‘geologic

agents’ impacting in rapid and profound ways on the past and future of not only

earth systems but also geology.

As an episode in a series of moments that invite

recognition of the multiplicity of time and perspectives, Silurian geology conveys the enduring impact of colonial capitalism

as a catastrophic event that covers its violence through the discourse of

progress while the soothing sound of rippling, bubbling water that runs

throughout the work is testament to the creek’s enduring flows in and throughout

earth time and submerged human practices of hearing its temporal flows, of

seeing things differently.

Essay by Therese Davis

(02) Dialogue

Dialogue between

Tributaries (Geoff Robinson, Ying-Lan Dann, Saskia Schut and Benjamin Woods) and Therese Davis, Taylor Mitchell

Therese Davis (TD): The conversation we're having this afternoon is a global conversation but deeply connected to First Nations’ Country. I am on Wurundjeri Woi-wurung, of the peoples of the Kulin Nation. I want to acknowledge them and pay respect to their elders, past, present and emerging and remind ourselves that it's always been Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land land and always will be.

Geoff Robinson (GR):

I'm also meeting on Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land in North Melbourne.

Ying-Lan Dann (YLD):

Thank you for your introduction Therese, I am also joining from Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land.

Saskia Schut (SS):

As am I—from North Fitzroy.

Benjamin Woods (BW):

Me too here in Parkville, on Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land.

Taylor Mitchell (TM): And a lot of the project that I have worked on so far has taken place on Wurundjeri Woi-wurung land.

Our first question is, can you please describe Tributaries and how silurian geology is situated within that project?

GR:

Maybe I can get the ball rolling a bit in terms of that placement. So Tributaries started as a conversation between Ying and myself along a submerged creek that runs through North Melbourne, where we both live in relation to. It was initially an audio work for Bus Projects; it started as us walking along, doing some research, trying to find the source of that submerged creek. We followed that creek from where we hypothesised the source was in Royal Park, through the urban terrain of North Melbourne and Parkville and its entry into Moonee Ponds Creek. That was the initial conversation walk we recorded and presented to Bus Radio. Then we invited Ben and Saskia into the project to build that further, looking into other tributaries, particularly in this area of Wurundjeri Woi-wurung Country and in proximity to Moonee Ponds Creek.

YLD:

Partly this was a chance encounter. Geoff and I were learning about the creek independently through our respective practices as an artist and architect before meeting one day at a local park called Gardiner Reserve, a catchment of the Moonee Ponds Creek. So this early iteration was partly about meeting as neighbours but also about emerging as collaborators through a shared interest in the layered conditions of where we lived.

GR:

So silurian geology. It was in the early stages, the first six months of 2021, we did a lot of research around the creek tributaries of Lower Moonee Ponds Creek, looking into drainage systems and redirected and submerged tributary creeks. Then we devised a series of walks we all went on—Saskia was joining us remotely from Sydney and via Zoom on the phone, which appears in silurian geology. And out of those walks, we had devices with us, and also different objects that engaged with the creek—sound recording, video recording—and a range of objects which maybe Ben you could talk a bit about in terms of the flutes. We edited these walks together and found particular moments we wanted to highlight—they became the episodes presented with Composite Moving Image and Bus Projects online at the end of 2021 and into 2022.

BW:

Shall I talk a bit about some of the material elements of the project as well? So as much as it was a research project that spiralled out of this engagement with water, there were times the walks themselves produced a research methodology where we were encountering things live and often through following our nose, in a way. And Saskia, joining us from Sydney, would ask, ‘what plant is this? Can I get closer to that with the phone?’ And you know, touch was involved in all of our engagements through this very material, attentive process. And Ying can speak more fully to some of the drawing elements that emerged within her practice engagement with place.

I was also interested in working sculpturally. As these things happen, you sort of roll into them in a research project, so I rolled into some burrow formations—sandy structures that perhaps would be structurally very important to the creek if it were not concreted. And so, I was working with glass as a foil for some imaginative underground activity and bringing that along in a sonic context with some of our walks.

YLD:

Thanks, Ben; yes, I think from my background as a drawer, walking became a way to perform in response and in conversation with the various durations and material conditions we encountered. Thinking of tributary as drawing, was also a way to re-consider how the region had been historically mapped and represented through a settler imaginary. There is a term that is used in geography, in relation to digital mapping, or geo-spatial information systems, called ‘ground truth’, which denotes the actuality of a specific, which often differs from its representations. We noticed—and literally felt—ground truths by walking and negotiating ground surfaces.

But silurian geology, perhaps Saskia can speak to how it moves into a discussion about the larger temporal elements going on in the works but also in our walks—things that we encountered that were beyond the less direct material engagements.

SS:

I think it’s interesting how you described that. You know, thinking about the idea of the subterranean in relationship to silurian geology—thinking how old silurian geology is, and the fact that it was formed when Australia was still part of the Gondwana continent, and the idea that it was formed at the bottom of an ocean trench and also at the time where there was a huge glacial melt. I was very interested in how things are submerged and emerge at different times and how that is constantly happening. It was very interesting for me. I was joining from afar, but through the methods we were using, it was surprisingly vibrant, and I did feel like I was joining the walks. I was just looking at some archival images of some of that Silurian cliff that has been exposed. So there are these weird images of that, and then live footage of Ying walking along and touching the surface of this geology. I think there are so many kinds of strange temporal collisions happening there. And maybe you can talk more to this Geoff when you pieced together the film.

GR:

I think just watching it again, then, I’m thinking of the different vantages. I’m on the other side of the creek, viewing Ying, which is the introductory shot. And obviously, we’re listening; we are hearing the creek. And then there is the image across from the creek, where we’re seeing Ying, the relationship with the silurian geology with the concrete cast in the seventies—I think it was around that period that it was channelled or canalled. Then Ying’s view through the phone of the detail of the geology and the graffiti in relation to that, and then Saskia’s relationship to that. Then introducing the image with the archival image as well, indicating the pre-concreted creek relationship. So there were these different views across time, but also spatially with these different positions and locations of viewing and interpreting. I think, in many ways, that particular video moment really does picture the nature of Tributaries as being these multiple sources and ways of thinking and experiencing this moment in time and place. It speaks a lot to an edited sequence—those different positionings and engagements.

SS:

Yeah, and that’s a really important project for me—these multiple perspectives. You’re constantly setting up a view, and then it gets ruptured and added on to, so there is this constant multiplying of perspective. This is a really important part of the work and how we work. It became interesting to me to think about different practices. I come from a landscape architecture background. Ying has an architecture and art background. You both have a, well, I don’t want to speak to your practices as artists, but you both have an interesting approach. So I think being able to think across all of these fields and knowledges and ways of knowing also helps to create the richness that comes through in this film—and all of the films.

YLD:

There is, I think, a sedimentary quality to the editing —like the geology we were enveloped within. We treated the images in a sedimentary way, adding and eroding layers.

BW:

And I think it also helps that we weren’t outcome-oriented, I guess. We were interested in the process leading the project. And as much as there were formats that we, especially given the pandemic, formats that the project lent itself to—moving image and sound—somewhere along the way it could have emerged, it continues to emerge as different things. It could have emerged as anything; to be honest, we had many different things on the stove as possibilities.

When I was looking into the guiding questions, I was thinking about how to consider films as an artifact, in a way. I was curious to hear from the group and from you as researchers what larger conversation there is around that. As a practitioner, I am not strictly exposed to these categories and these points of framing the work.

GR:

It’s interesting that the first walk we arranged, not the initial one, but the one with the four of us, I think we had a recorder as we were walking, but we didn’t go to document or ‘capture’ anything. So that was quite interesting as an initial starting point of just being present and talking. Then we brought along the phones, video cameras and sound recordings, with the intention of using those on consecutive walks.

SS:

And as you're working with cameras and sound and hearing, you sort of falter with the word ‘capturing’—how do you use the lenses and these tools not in a way that is necessarily objectifying? How do you continue with that situated, place-based way of working? And I think that's a curious thing for me to kind of think about. I know you were interested in the contrast between the colonial visual archive and handheld documentation—I would argue that they're both colonial. So how do you consciously work with that, perhaps, with at least a question of what it's doing?

BW:

Yeah, absolutely. And perhaps even gather some intention around it. With the quote that appears in a different episode of the project, from construction projects along the creek. We were all kind of grappling with the tone of it. The paradigm that comes with it, that we certainly inherit and we certainly have to, at the very least, acknowledge.

YLD:

I think Saskia has raised a really important point that recurred in various ways over the walks—How do you register environmental conditions in a manner that is generative and collaborative so that the context is a conversationalist rather than a subject of our assumptions and narratives? This was one of the motivations for our experiments with copper pipe, which was literally a conduit for listening to the gurgling water. Pipes exist to channel water toward and away from human populations; in this iteration, it is deliberately used to bridge communication between us.

TD: Ben, I was going to answer your question regarding my interests if you’d like me to. One of the things that I think about this project is that it disrupts ideas, particularly ideas about temporal relations in documentary. So, juxtaposing the documentary black and white photograph with the mobile moving image disrupts that idea of the filmic documentary’s privileged relation to the past—that is, it captures what was there in and through the indexicality of the image; it’s captured, it’s frozen, a little bit fossilized, like the once-living things that have left their impression in the sediments of the rock I’m interested in how you’re using the mobile camera for enlivening the images and making sure we think about how rocks change, that they’re transformative, that they’re always decomposing, recomposing. The way that you do that gives us this other method of documenting. This method that you’re using of walking and moving is doing something very interesting, I think, in terms of documentary practice.

BW: Thank you, that’s really rich.

TD: And this comes back to our project about documenting environments. A lot of work regarding urban environments can have a very singular focus—either showing the living or showing what has been destroyed. But I think this project is about finding the remnants and what remains and examining the interfaces of that. That it's not all good, and not all bad—humans and nature are entangled.

SS:

Yeah. And you know, Anna Tsing calls that ‘the ruins of capitalism’. I love that term. It’s so deeply entangled. We wanted to bring that through the films—the legacy you can see in the remnants. Ecology is constantly remaking itself, and [the project] explored how we might document those historical and cultural legacies you can see continuing while still finding some joy. We would find these beautiful moments of sound and life thriving in the waterways.

BW:

Even something that I would overlook, but Saskia sees, is the algae of the growth in the concrete that was really fascinating and alive.

GR:

And those moments of literally experiencing the creek's water, where there was a particularly damp area with little mosses growing around this grill or gutter. There is one street in particular where we started in West Brunswick with a veneer of the concrete street and gutters and drains and houses, with planting down the centre of a particular eucalypt with a dark sap that is not particularly indigenous to that specific location, but it's flourishing. There were these beautiful, huge trees. I also think about Plane Tree Way, which is just out my window. The initial conversation with Ying was about plane trees thriving in this particular location—there's a creek between them—all of the modes and ways of experiencing the creek through these relationships.

YLD:

On that, a funny anecdote I have from speaking to our other Plane Tree Way neighbours was that in the 1980s, the stream was so prone to flooding that the City Gardens Complex where Geoff lives, which was designed by the architect Peter McIntryre, would inundate and cars in the lower ground car park literally bobbed against the ceiling. I love this image of the stream just going where it wants to go.

BW:

Yeah, I think there was a delicate relationship. Sometimes I felt that we were... not nostalgic, but there was a particular question that carried through in our walks: what are we looking for? And perhaps even a kind of white melancholy can creep into that as a kind of reflection of ‘oh, what have we done?’ I can't speak to that for the whole group, but I remember feeling a particular kind of thing which was, ‘What is the particular lens that is following me through my walk?’ And obviously, that is multiple and changing, and all different perspectives are part of that.

SS:

Following that, I think it's also interesting to think about this idea of how we position it. We do it as well, like, you know, these waterways are hidden, submerged, etc. And, you know, in a way, they are, and maybe they're hardest to see. Is it a lens that we perpetuate this invisibility of like these living water entities that, in a way, is what the colonists, you know, arrived with as well? Yeah, so I am sort of conscious of that as well, in the language we're using, and in a way, the works are not necessarily ‘revealing’ or say that things are not there. But maybe it's just about generating ways to be able to see.

TD: What I think is interesting in your video is that you get, on the one hand, a juxtaposition between the cement structure imposed on the landscape as the storm drain and the sandstone, and also a kind of continuity in that they're both forms of rock or part of rock formations.

SS:

Yeah, the water would have created the initial sort of, you know, river course. And then, you know, and, you know, the geology that kind of, holds that watercourse, and then yeah, this added layer of the concrete, that does it again, but in a much more severe way. And I think what's really interesting to me is when that happens, it becomes an entirely different speed of water. So it goes from being a sort of slower water to all of a sudden, it's all about getting the water away as quickly as possible. I read in one of their documents that the council wanted to change some of the practices in relationship to water, and there was a cultural consultation. One of the things that came out of that was this idea of climate flows because that's where you create some of the ecologies from pre-colonisation. I think it's really interesting thinking about the different speeds that those different rocks have allowed, disallowed, or changed.

GR:

And then in the generating of those rocks, the geology is like, such a deep time formation, where concrete is actually poured quite quickly, and the components are put together quite quickly, and it's a very, radically different sort of forming of rock.

SS:

And then, of course, you know, the thing that's also happening is that the concrete is being eroded as well. And, you know, we've seen lots of evidence of that. And then, within that, there's the water that will merge and remake, you know.

YLD:

This really interests me in terms of asphalt and road design. When you look across a section of a road, you can detect a curvature, which runs the stormwater off into culverts and causes all sorts of problems during torrential rain. By contrast, when water lands on soil, it slowly permeates. That said, asphalt is also very thin and manipulable. Some of you may know that as well as its use for asphalting, bitumen is also the medium used in etching. Rather than thinking about asphalt as impermeable, I find it interesting to think about it as a surface for etching - all the water that lands on it finds courses to the sub-surface and eventually opens up to cracks where mosses flourish.

GR:

It's quite remarkable in sections of the concreted sections of Moonee Ponds, Creek, the plants that grow up in the cracks, like we sort of experienced, I forget the scientific name, but on the Sheoak, trees cropping up. And the uneven callistemon and eucalypt sort of popping up through, and it's quite extraordinary this coming up through the cracks of all the plants or seeds that might be sort of running through the uncompleted channel, these are the ones that are actually sort of coming up through the gaps in the concrete.

SS:

In talking about that speed, we did several walks where we started from a higher point and then walked down to a low point. And so essentially following the flow of the water. We made a conscious decision for the longest version of the film, which I think also comes out in the smaller sections, to disrupt and not necessarily follow that flow—that’s something as well, in the way that we experience time and temporality.

And a lot of the footage of us walking, we’re not really going anywhere, we never sort of arrive anywhere.

BW:

And how attention is also steered by the different paces of the water as well, you know the sort of Trin Warren Tam-Boore waterhole space definitely lends itself to a very different kind of attention—the kind of gum walk that I missed as a member, but that was such a beautiful pooling in one area, as well.

TD: I watched the videos last night on Composite—jumping around. I want to say that the episodic structure works well, that it's not a narrative. And this sort of goes back to what you were saying, Saskia, about mapping. Even the original audio walk, even though it's following the creek, it's not a linear narrative of a journey, and it's not a mapping, it's episodic, and I guess that's what you're saying, Ben. Would you like to say more about that, particularly how it is presented on Composite?

GR:

I think that came directly from what occurred on the walks. There was an idea about having five half-hour episodes that were potentially a particular walk each. And we got to the point of editing them in that sequence, and we were always thinking, What is happening here? What is this sequence that we’ve created, and what was experienced on the walk? And it always came down to if there was a concentration of engagement— whether through a camera lens or a microphone—that there was a lot of focus on that particular moment in time and place, and we started to think a lot about those moments. And we ended up calling them video moments. Rather than episodes or short films or anything, they were moments. They concentrated on moments where we paused and spent time engaging through these various modes of listening, viewing, touching, and smelling.

TD: And drawing? That beautiful piece, the yellow box gully, where Ying traces the shadows, it’s amazing, that image.

YLD:

Thanks, Therese. It was a singular episode, but it was, like the other processes we have discussed, entirely unplanned. I had taken a length of paper on the walk and actually felt quite awkward because it had a different feel to walking as drawing. I didn’t want to fall into the trap of scaling the world down, so when I rolled the paper out, I was really just carrying on the practices of moving that we had established by literally negotiating where our feet fell while walking. Drawing in this way showed the interplay between the sun, tree, my body and the ground. Going back to our earlier conversation about multiplicity, this process allows - I hope - some of the multiplicity and dynamism of the place to come through.

GR:

Yeah. It's that beautiful, showing that shifting of the earth's movement, as opposed to what it's doing, when you watch in detail that footage, and that other side of the drawings, she is still drawing the line of the shadow, five-ten minutes later, so it's showing that shift. The relationship was happening simultaneously when Saskia and you, and I were focusing on a particular river red gum near where Ying was drawing. I love how you talk about that Saskia, about the twist of the tree having a relationship to the turning of the earth.

SS:

I was thinking a lot in that work with this idea of circling. And so she does this thing where she sort of circling her hips at one stage, and we make this sort of circle around the tree. Because I think that's kind of a nice, you know, it's another sort of metaphor way or way of thinking about a sort of a ‘swarming’.I mean, the reason why we found ourselves up there, which is this area where there's kind of remnant pre-settlement sedimentation, was that we noticed on one of the archival maps there a sort of an indication that there was a Creek line at some point, I think in Australia, and specifically around Victoria, there are quite a few similar creek lines. There is this idea that maybe some of them missed being marked because one year they weren't there—or there was ‘no evidence’ of them being there or at least to white eyes. I think that is quite interesting in this site that, you know, doesn't look at all like it has ‘water’—but then thinking about the way that the red gum, you know, traditionally indicates water. So yeah, just finding other ways to see that water.

Regarding that turning, I've been looking at trees in the way they twist, and they tend to twist mainly in their anticlockwise. And from what I've understood, and from what I've read—I am getting different versions of this—it is partly to do with the position of the sun and the dominant wind conditions. So in a way, you can read the relationship of the tree twisting as the much larger forces and movements on a planetary scale.And you can think about water in that way because the water is being drawn up the tree.

BW:

Yeah.

SS:

So I think also thinking about water not just being in the waterways, but you know is that it's also, you know, moving upwards through the trees. And then, yeah, in so many different ways.

BW:

It's amazing because it reminded me that in our first walk, which we didn't video very much, we were hugging River Red Gums to see how old they were by approximate age. One year to 1cm. So we were hugging the trees in that moment in the yellow box gully, it was kind of a delicate touch.

TD: This has been amazing. I feel like maybe the circle image is a nice way to circle back to where we started, just to see if, Taylor, there is anything you want to pick up on.

TM: One thing I’d love to chat about is how the work engages the notion of what you can’t see. Specifically, given your focus on Moonee Ponds Creek, which is also a stormwater drain on which the infrastructures are mostly underground and out of sight and sort of juxtaposed with these temporal layers of the ancient rock formation as well—how does the project engage with ideas about what is below the surface? And I guess the idea is of interfaces more broadly.

BW:

I'll open by saying these temporal layers keep spiralling, like what Saskia was talking about the tree in relation to the sun in relation to the wind. There are so many different layers of temporality there that I feel like it's just this continuing and unfolding. More dimensions, more dimensions, and more that are beyond my comprehension. And something about that speaks to the spatiality of the place as well—that there's something that, you know, very easily we think we've instrumentalist and controlled, but instead, it's seeping through with its constant forces. And there's something about even the slightest opening up of the slightest crack. Even the Friends of Moonee Ponds Creek were like, ‘Ooh, we see some cracks there. Maybe we could flip that piece of concrete over. You know, what would that do?’ Another walk would be a great opportunity to continue that attention opening.

GR:

When thinking of the submerged and emerged relationship, we were thinking around it as the colonial act of control through channelling water and making it stable for building houses and so forth. But, that submersion is more layered and intricate than just the colonial. Just thinking about this rupture of the submergence and the piping and concrete. There is a word that is used a lot:‘seepage’.

TD: Have you been thinking about your methods and all of the various vantages in the walking, in relation to Country, as a way of being in these spaces?

GR:

We were also aware of our positions regarding our heritage and white settler or migrant experience with Country. And as part of this, we did go through a consultation process with the Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Association with Auntie Gail and Auntie Julliet which was really interesting and insightful conversations that we had. And that is something that we wanted to do early on, and seek permission for our recording methods and how to record respectfully. So these were conversations that we were keen to have and were really valuable.

BW:

Yeah, I suppose they are also conversations we hope to continue as we keep working. They were generous conversations, especially regarding leaving that question open—how do we respectfully engage on Country in our project or more broadly in our lives? I remember us asking, Can we seek permission to record? and Auntie Gail said, ‘I think we can do that’. And I remember thinking, oh, this is a people-to-people thing; it's not a form that you get as part of a bureaucratic process. It’s a question you get invited to keep asking, not something you get once and for all. And something about that was sensitising. Even beginning the consultation process makes the project more sensitive, in its attention to place perhaps, and certainly in its attention to our particular cultural perspectives.

SS:

Geoff and I went to a conference about the rights of water. And I think that's something that I carry with me. So, you know, even though it's really troubled, complicated—the water swelling from Moonee Ponds. I think it is worth thinking of a sort of sacred water that has life and treating it as such or practising what it might look like or what it might be from a settler perspective. The way several stories that I read along the way, including one where they describe where settlers arrive, and the ships were coming into Port Phillip Bay, and they were, you know, throwing the sheep overboard, and the sheep were swimming to shore. And they sort of made their way up Moonee Ponds Creek, and you know Maribyrnong and much of the life was very delicate ecologies that were thriving in those waterways. And engaging with those stories is always incredibly revealing.

GR:

Yes, the conference was incredibly rich, and there was a really strong First Nations presence in terms of speakers, and being on the water was quite amazing, being on a boat in the Sydney Harbour and talking about the Parramatta River coming into the harbour.

BW:

It does make me think of some landmark kind of moments, like the Te Awa Tupa, which is the document produced for the Whanganui River in Aotearoa, and how that was written both in the ‘crown’ language and Maori language of the Whanganui Iwi along the river. I guess that in itself was a kind of a landmark settlement of reparation for that river, in a way, and also a very major piece of legislation that means the power is redistributed from the crown. The power over the river, and the power of the river, as well. Something about that, I know that’s been a discussion about Birrarung; I’m not sure about Parramatta. I can’t help but think of that very big legal moment.

SS:

Because that’s in the favour of actually doing something rather than being a system that completely marginalises and oppresses; it’s one of the only productive spaces that colonialism could ever have.

The key collaborators for Tributaries are architect and artist Ying-Lan Dann, artist Geoff Robinson, landscape architect and artist Saskia Schut, and artist Benjamin Woods. Iterations of Tributaries have been presented at Bus Projects Radio (2020), Composite Moving Image Agency (2022), with up and coming presentations at Open Nature/Open House Melbourne (2023).

tributariescollective.net @tributariescollective

Geoff Robinson is a Narrm/Melbourne based artist who creates situated projects that engage listening as a process for unravelling the durational layers of place. Robinson’s practice develops comparative relationships between multiple situations and places as a way of understanding deep time, current, and future relations to place. geoffrobinsonprojects.com

Saskia Schut’s research addresses climate uncertainty and extreme Planetary distress through intimacy, relationality and embodiment. She investigates the ecological, historical and cultural legacies that are continuing to shape the urban environment.

Benjamin Woods is an artist who practises with training in sculpture and sound. He explores how embodied relationships with sonic objects can generate attention to relational and ecological connections. Woods has been exhibiting and performing for over ten years and recently completed a PhD project at Monash University focusing on fragile ecologies of practice.